Imagine rules like this one defining a landscape, where maintainable code lives in the valleys. As you add new behavior, it’s like rain landing on your code. Initially you put it wherever it lands. Then you refactor to allow the forces of good design to push the behavior around until it all ends up in the valleys.

TL; DR

I once had to design classes for a configuration and resource manager, where there are different kinds of resources or configurations all sharing a similar structure and behavior with a little difference in some fields. But mostly the functionality would be same for all these resources.

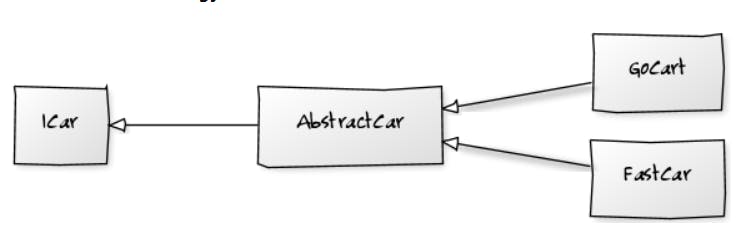

Considering the pros, cons and ideal use cases for interfaces and abstract classes; and what was more suitable for this scenario, I went with abstract class as the base for these classes, since these were a group of closely related classes with some behavioral differences.

I was almost through with the implementation, when I came across this post from Stack overflow (as we all do at some point in our day). Basically, the answers all advised to not use Abstract classes at all. And the answer from Nigel Thorne almost led me to refactor my code. But the same answer also made me wait and let my code age.

The only two uses of Abstract class

Abstract classes are used in one-of-two or a combination of the following two ways.

Abstract Classes for providing flexible behavior for related classes

If the child classes have a common interface, it means you are using inheritance to change certain behavior. It is usually advisable to prefer Composition over Inheritance.

Thus, you should try strategy pattern for tweaking the behavior.

Abstract Classes as a helper class

If it is some common functionality which you want to share among these classes, it is better to move this functionality to a concrete class instead.

Abstract Class as a Stepping Stone

Going back to my use-case from the beginning of this blog post. Even though I was using Abstract Classes for providing flexible behavior for related classes and also Abstract Classes as a helper class, a little. If I went with implementing a third class as a utility to be consumed in all these classes, I would have more useless code for initializing these objects and calling the methods instead of the logic. Hence, I decided to go with the Abstract class.

As the code and requirements evolved, I made the base class as concrete and more dynamic and removed the child classes. I now only have to use a child class for very specific scenarios. But that might change too.

Sometimes on this journey towards perfection, bad code can lead to good code.

A beautiful excerpt from Nigel Thorne’s answer to How to Unit Test Abstract Classes?

Update 2: Abstract Classes as a stepping stone (2014/06/12)

I had a situation the other day where I used abstract, so I’d like to explore why.

We have a standard format for our configuration files. This particular tool has 3 configuration files all in that format. I wanted a strongly typed class for each setting file so, through dependency injection, a class could ask for the settings it cared about.

I implemented this by having an abstract base class that knows how to parse the settings files formats and derived classes that exposed those same methods but encapsulated the location of the settings file.

I could have written a “SettingsFileParser” that the 3 classes wrapped, and then delegated through to the base class to expose the data access methods. I chose not to do this yet as it would lead to 3 derived classes with more delegation code in them than anything else.

However, as this code evolves and the consumers of each of these settings classes become clearer. Each settings user will ask for some settings and transform them in some way (as settings are text, they may wrap them in objects of convert them to numbers etc.). As this happens, I will start to extract this logic into data manipulation methods and push them back onto the strongly typed settings classes. This will lead to a higher-level interface for each set of settings, that is eventually no longer aware it’s dealing with ‘settings’.

At this point the strongly typed settings classes will no longer need the “getter” methods that expose the underlying ‘settings’ implementation.

At that point I would no longer want their public interface to include the settings accessor methods; so, I will change this class to encapsulate a settings parser class instead of deriving from it.

The Abstract class is therefore: a way for me to avoid delegation code at the moment, and a marker in the code to remind me to change the design later. I may never get to it, so it may live a good while… only the code can tell.

I find this to be true with any rule… like “no static methods” or “no private methods”. They indicate a smell in the code… and that’s good. It keeps you looking for the abstraction that you have missed… and lets you carry on providing value to your customer in the meantime.

I imagine rules like this one defining a landscape, where maintainable code lives in the valleys. As you add new behavior, it’s like rain landing on your code. Initially you put it wherever it lands. Then you refactor to allow the forces of good design to push the behavior around until it all ends up in the valleys.